StackWarp: Exploiting Stack Layout Vulnerabilities in Modern Processors

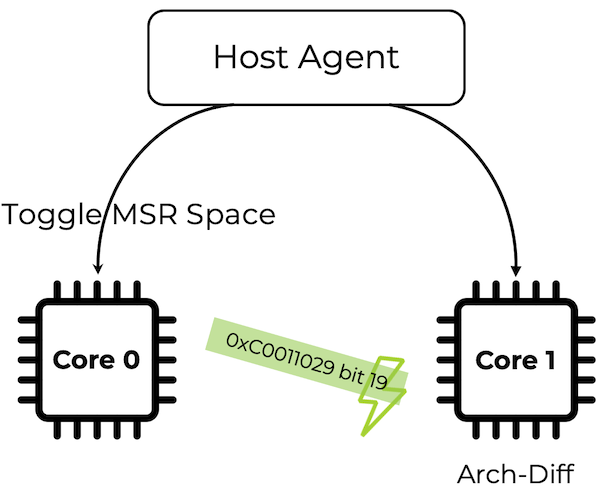

Today we are disclosing a novel CPU bug affecting AMD Zen 1-5 microarchitectures. By toggling undocumented Model-Specific Registers (MSRs) from a sibling logical core, an attacker can induce arbitrary architectural offset into the stack pointer (%rsp) of a victim process.

# The “Chicken Bit” Rabbit Hole

In the x86 world, MSRs are the “under the hood” control surface. They handle performance counters, debug hooks, and the infamous “chicken bits”—latches used by engineers to disable buggy logic without a full hardware respin.

We’ve seen interest in this space before: Chips and Cheese recently documented the perf/power trade-offs of disabling the Zen 4 Op Cache. Usually, these bits are set-and-forget at boot. But what happens if you toggle these bits dynamically while a process is mid-pipeline?

We already know that messing with MSRs can be dangerous. Projects like MSRTemplating by Kogler et al. and msrscan by Tavis Ormandy have shown that fuzzing these bits usually just freezes the CPU or hangs the system.

In the security world, a crash is loud and easy to spot. We wanted to find something more subtle, something beyond mere instability. Our goal wasn’t to break the core, but to find an MSR bit that silently affects the CPU’s execution state without crashing it.

# The Discovery: From MSR Fuzzing to Targeted SMT Attacks

We began with a simple, brute-force hypothesis: what happens if we toggle undocumented MSR bits while the system is under load?

Initially, we just ran a fuzzer that randomly flipped MSR bits on a single CPU thread to see what would stick. It was noisy, but mostly just frustrating. We saw plenty of kernel panics and machine check exceptions (MCEs), but nothing that looked like a controlled primitive.

The breakthrough happened when we looked at MSR Scope. According to the AMD manuals, many MSRs are core-scope, meaning they are shared between the two logical threads (SMT) of a single physical core (Hyperthreading called by Intel). That is, when you modify an MSR on one logical core, the change is instantly visible to its sibling.

We then refined our approach into a synchronized sibling attack:

- The Victim: A user-space process pinned to Logical Core X.

- The Fuzzer: A tight loop pinned to Sibling Core Y, rapidly toggling bits across the MSR space.

By avoiding context switches and keeping the victim “hot”, we immediately observed segmentation faults on the victim process. Specifically, toggling bit 19 of MSR 0xC0011029 (on Zen 4) caused the victim to crash almost instantly.

# Analysis: Where did %rsp go?

Inspecting the core dumps via GDB revealed a classic stack imbalance. At the point of a ret instruction, the stack pointer had shifted. The CPU was popping return addresses from memory it shouldn’t have been touching, leading to jumps to 0x0 or addresses located mid-stack.

Since ret only fetches the return address from what %rsp tells it to, the imbalance had to happen earlier. Did a previous push/pop fail in the prologue or epilogue?

We hypothesized two possible failure modes for e.g., a push instruction during an MSR toggle:

- Instruction Drop: The

pushis skipped entirely. - Partial Execution: The store to memory happens, but the architectural register, rsp, update is lost.

To determine the exact nature of the failure, we designed a naked function to maximize the race window and inspect the side effects in memory:

#define ASM(S) asm volatile(S)

__attribute__((naked)) void f1(void* addr) {

ASM(

/* Phase 1: Clean the Stack Slots */

"mov rdi, 0\n\t"

".rept 8\n\t"

"push rdi\n\t" // Fill stack slots with 0

".endr\n\t"

"add rsp, 0x40\n\t" // Reset stack pointer

/* Phase 2: Fill the Stack Slots with 0x1337 */

"mov rdi, 0x1337\n\t"

".rept 8\n\t"

"push rdi\n\t"

"mfence\n\tmfence\n\tmfence\n\tmfence\n\tmfence\n\tmfence\n\t"

".endr\n\t"

"add rsp, 0x40\n\t"

"ret\n\t");

}

With this code, we first push 0 onto the stack eight times and then reset %rsp. This ensures that any 0x1337 we find later is the result of a new push, not stale data.

We then push 0x1337 eight times. We use aggressive mfence padding between each push. This increases the probability that the attacker’s MSR toggle on the sibling thread hits one of the push rdi iterations.

The result: Inspecting the memory revealed that all eight 0x1337 values were correctly written to the stack. However, %rsp did not reflect eight subtractions. The instruction’s memory $\mu$op executed correctly, but the stack pointer update was discarded.

# Breaking the Stack Engine

While examining the microarchitecture optimizations, one named Stack Engine pops up:

The processor has an efficient stack engine that renames the stack pointer. It is placed after the μop queue. Push and pop instructions use only a single μop. These instructions have zero latency with respect to the stack pointer, so that subsequent instructions that depend on the stack pointer […] are not delayed.

This matched our observations perfectly. The Stack Engine holds a speculative delta for the stack pointer which is synchronized with the architectural register file later. Toggling this undocumented MSR bit disables the engine, causing the speculative delta to fail to update correctly.

To confirm that Bit 19 of 0xc0011029 is indeed the “Stack Engine Enable” chicken bit, we conducted a performance counter analysis on an AMD EPYC 9124 (Zen 4). The results show a clear shift in how the microarchitecture handles stack-relative instructions:

| Category | Instruction | Bit=0 (Default) | Bit=1 (Disabled) | Obs. Delta |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stack (Implicit) | push REG | 1 $\mu$op | 2 $\mu$ops | +1 $\mu$op |

pop REG | 1 $\mu$op | 2 $\mu$ops | +1 $\mu$op | |

call + ret | 5 $\mu$ops | 11 $\mu$ops | +6 $\mu$ops | |

| Stack (Explicit) | add rsp, IMM8 | 2 $\mu$ops | 1 $\mu$op | -1 $\mu$op |

mov rsp, REG | 2 $\mu$ops | 1 $\mu$op | -1 $\mu$op | |

| Non-Stack | sub rdi, IMM8 | 1 $\mu$op | 1 $\mu$op | No Change |

The smoking gun: When the Stack Engine is enabled (Bit=0), an explicit instruction like add rsp, 8 actually costs more $\mu$ops. This occurs because the CPU must issue a synchronization $\mu$op to merge the Stack Engine’s speculative delta back into the architectural %rsp register.

When the engine is disabled (Bit=1), that sync is no longer required, and the instruction count drops to its raw decoded state.

In contrast, push and pop now need one extra $\mu$op to update the stack pointer.

Further technical specifics on the underlying stack engine can be found in the concurrent research from ETHz, which provides an exhaustive deep dive into its internal structure.

# The “Frozen Delta” Effect

The most dangerous aspect of this bug is how the CPU handles the transition between these two states. We discovered that the speculative delta held by the Stack Engine doesn’t just evaporate when the engine is disabled—it freezes.

We found that if disabling the engine leads to a crash, re-enabling it later leads to a second crash. The behavior is mathematically symmetric:

- If disabling the engine induces a $+0x10$ offset.

- Re-enabling the engine later induces a $-0x10$ offset.

This basically means the speculative delta is frozen while the stack engine is unexpectedly disabled by the hyperthreading. And the delta is immediately released when the stack engine is enabled again.

For example, if two push instructions fail to update the stack pointer, the process will likely crash because the stack pointer ends up with a $+0x10$ offset. Since the program expects the stack to stay balanced, this misalignment causes problems.

When the stack engine is enabled by the hyperthreading, the original $-0x10$ offset from the two push instructions gets released back to the current process, which can lead to another crash.

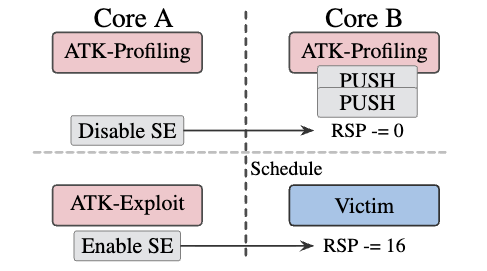

# StackWarp

The “Frozen Delta” gives the attacker a mechanism for precise control over the stack offset, a vulnerability we name StackWarp.

See the attack profiling phase on the core B, the attacker can use a loop of push/pop instructions to generate a desired faulted offset.

- Direction: Controlled by choosing either PUSH (negative offset) or POP (positive offset).

- Magnitude: Controlled by the number of instructions executed in the loop while the engine is toggled.

This primitive is especially common in virtualization scenarios. In the context of Confidential Virtual Machines, while the attacker controls a sibling thread. The profiling phase can be hidden within the interrupt handler of a malicious hypervisor, allowing the attacker to “prime” the Stack Engine with a specific offset before releasing it onto the victim.

Demos and the TL;DR are up at stackwarp website. If you’re looking for the full technical details, you can grab the full research paper and our code here.

# Mitigation

While the underlying bug exists across Zen 1-5, it only poses a security risk in specific scenarios with a privileged attacker, like confidential computing. We did responsible disclosure to AMD in March 2025. AMD assigned CVE-2025-29943 and embargoed the findings until January 15, 2026. Prior to the public disclosure, AMD confirmed that hot-loadable microcode patches have already been released to their customers.